This explains a lot about the Great Society:http://www.pbs.org/johngardner/chapters/4c.html

Archive for the ‘Reform’ Category

4 Feb

From The Shame of the Cities

From The Shame of the Cities, 1904, Lincoln Steffens

Perhaps the most influential of the muckrakers was Lincoln Steffens. Steffens’ articles were published in McClure’s magazine in 1902 and 1903 and then collected in The Shame of the Cities, published in 1904.

As you read, consider these questions:

1. What is Steffens’ opinion regarding businessmen?

2. What is Steffens’ opinion regarding politics in America?

3. What influence did Steffens think business had on politics?

4. Were Steffens’ criticisms accurate in 1904? Are they accurate now?

______________________________________________

Now, the typical American citizen is the business man. The typical business man is a bad citizen; he is busy. If he is a “big business man” and very busy, he does not neglect, he is busy with politics, oh, very busy and very businesslike. I found him buying boodlers in St. Louis, defending grafters in Minneapolis, originating corruption in Pittsburgh, sharing with bosses in Philadelphia, deploring reform in Chicago, and beating good government with corruption funds in New York. He is a self-righteous fraud, this big business man. He is the chief source of corruption, and it were a boon if he would neglect politics. But he is not the business man that neglects politics; that worthy is the good citizen, the typical business man. He too is busy, he is the one that has no use and therefore no time for politics. When his neglect has permitted bad government to go so far that he can be stirred to action, he is unhappy, and he looks around for a cure that shall be quick, so that he may hurry back to the shop.

Naturally, too, when he talks politics, he talks shop. His patent remedy is quack; it is business. “Give us a business man,” he says (“like me,” he means). “Let him introduce business methods into politics and government; then I shall be left alone to attend to my business.” There is hardly an office from United States Senator down to Alderman in any part of the country to which the business man has not been elected; yet politics remains corrupt, government pretty bad, and the selfish citizen has to hold himself in readiness like the old volunteer firemen to rush forth at any hour, in any weather, to prevent the fire; and he goes out sometimes and he puts out the fire (after the damage is done) and he goes back to the shop sighing for the business man in politics. The business man has failed in politics as he has in citizenship. Why? Because politics is business.

That’s what’s the matter with it. That’s what’s the matter with everything,—art , literature, religion, journalism, law, medicine,—they’re all business, and all—as you see them. Make politics a sport, as they do in England, or a profession, as they do in Germany, and we’ll have—well, something else than we have now,—if we want it, which is another question. But don’t try to reform politics with the banker, the lawyer, and the dry-goods merchant, for these are business men and there are two great hindrances to their achievement of reform: one is that they are different from, but no better than, the politicians; the other is that politics is not “their line”. …

The commercial spirit is the spirit of profit, not patriotism; of credit, not honor; of individual gain, not national prosperity; of trade and dickering, not principle. “My business is sacred,” says the business man in his heart. “Whatever prospers my business, is good; it must be. Whatever hinders it, is wrong; it must be. A bribe is bad, that is, it is a bad thing to take; but it is not so bad to give one, not if it is necessary to my business.” “Business is business” is not a political sentiment, but our politician has caught it. He takes essentially the same view of the bribe, only he saves his self-respect by piling all his contempt upon the bribe-giver and he has the great advantage of candor. “It is wrong, maybe,” he says, ‘but if a rich merchant can afford to do business with me for the sake of a convenience or to increase his already great wealth, I can afford, for the sake of living, to meet him half way. I make no pretensions to virtue, not even on Sunday.”

And as for giving bad government or good, how about the merchant who gives bad goods or good goods, according to the demand? But there is hope, not alone despair, in the commer-cialism of our politics. If our political leaders are to be always a lot of political merchants, they will supply any demand we may create. All we have to do is to establish a steady demand for good government. The boss has us split up into parties. To him parties are nothing but means to his corrupt ends. He ‘bolts” his parry, but we must not; the bribe-giver changes his party, from one election to another, from one county to another, from one city to another, but the honest voter must not.

Why? Because if the honest voter cared no more for his party than the politician and the grafter, their the honest vote would govern, and that would be bad—for graft. It is idiotic, this devotion to a machine that is used to take our sovereignty from us.

If we would leave parties to the politicians, and would vote not for the party, not even for men, but for the city, and the State, and the nation, we should rule parties, and cities, and States, and nation. If we would vote in mass on the more promising ticket, or, if the two are equally bad, would throw out the party that is in, and wait till the next election and then throw out the other parry that is in—then, I say, the commercial politician would feel a demand for good government and he would supply it. That process would take a generation or more to complete, for the politicians now really do not know what good government is. But it has taken as long to develop bad government, and the politicians know what that is. If it would not “go,” they would offer something else, and, if the demand Were steady, they, being so commercial, would “deliver the goods.”

2 Nov

William Lloyd Garrison, radical abolitionist

From the PBS series Africans in America, here is a simple biography of William Lloyd Garrison: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4p1561.html

See pp. 386-390 in your text for more information.

2 Nov

Quotes from Civil Disobedience

From Thoreau’s masterpiece!

I heartily accept the motto, “That government is best which governs least”; and I should like to see it acted up to more rapidly and systematically.Carried out, it finally amounts to this, which also I believe–“That government is best which governs not at all”; and when men are prepared for it, that will be the kind of government which the will have. Government is at best but an expedient; but most governments are usually, and all governments are sometimes, inexpedient. (opening lines)

______________________________________________________

But, to speak practically and as a citizen, unlike those who call themselves no-government men, I ask for, not at one no government, but at once a better government. Let every man make known what kind of government would command his respect, and that will be one step toward obtaining it.

After all, the practical reason why, when the power is once in the hands of the people, a majority are permitted, and for a long period continue, to rule is not because they are most likely to be in the right, nor because this seems fairest to the minority, but because they are physically the strongest. But a government in which the majority rule in all cases can not be based on justice, even as far as men understand it.

_______________________________________________________

Unjust laws exist: shall we be content to obey them, or shall we endeavor to amend them, and obey them until we have succeeded, or shall we transgress them at once? Men, generally, under such a government as this, think that they ought to wait until they have persuaded the majority to alter them. They think that, if they should resist, the remedy would be worse than the evil. But it is the fault of the government itself that the remedy is worse than the evil. It makes it worse. Why is it not more apt to anticipate and provide for reform? Why does it not cherish its wise minority? Why does it cry and resist before it is hurt? Why does it not encourage its citizens to put out its faults, and do better than it would have them? Why does it always crucify Christ and excommunicate Copernicus and Luther, and pronounce Washington and Franklin rebels?

________________________________________________________

Under a government which imprisons any unjustly, the true place for a just man is also a prison.

________________________________________________________

A minority is powerless while it conforms to the majority; it is not even a minority then; but it is irresistible when it clogs by its whole weight. If the alternative is to keep all just men in prison, or give up war and slavery, the State will not hesitate which to choose. If a thousand men were not to pay their tax bills this year, that would not be a violent and bloody measure, as it would be to pay them, and enable the State to commit violence and shed innocent blood. This is, in fact, the definition of a peaceable revolution, if any such is possible.

__________________________________________________________

I have paid no poll tax for six years. I was put into a jail once on this account, for one night; and, as I stood considering the walls of solid stone, two or three feet thick, the door of wood and iron, a foot thick, and the iron grating which strained the light, I could not help being struck with the foolishness of that institution which treated my as if I were mere flesh and blood and bones, to be locked up. I wondered that it should have concluded at length that this was the best use it could put me to, and had never thought to avail itself of my services in some way. I saw that, if there was a wall of stone between me and my townsmen, there was a still more difficult one to climb or break through before they could get to be as free as I was. I did nor for a moment feel confined, and the walls seemed a great waste of stone and mortar.

__________________________________________________________

(For the entire essay, click here: http://www.transcendentalists.com/civil_disobedience.htm)

1 Nov

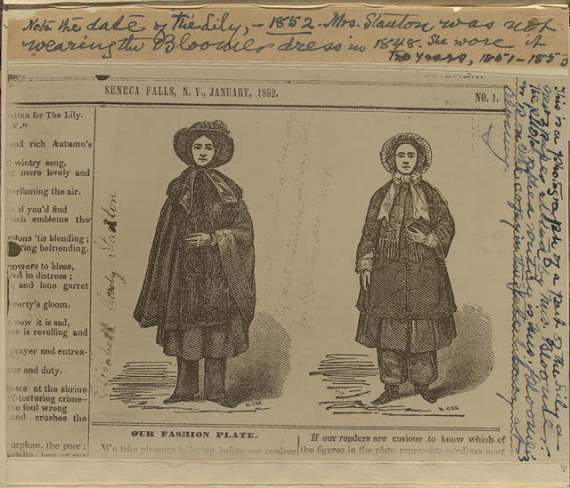

Amelia Bloomer and radical fashions from the mid-19th century

From an excellent exhibit at the American Memory Project at the Library of Congress.

Who was Amelia Bloomer? Here’s a biography from the National Women’s Hall of Fame:

“It was a needed instrument to spread abroad the truth of a new gospel to woman, and I could not withhold my hand to stay the work I had begun. I saw not the end from the beginning and dreamed where to my propositions to society would lead me,” said Amelia Bloomer, describing her feelings as the first woman to own, operate and edit a newspaper for women. Bloomer, a woman of modest means and little education, nevertheless felt driven to work against social injustice and inequity — and her personal convictions inspired countless other women to similar efforts.

Bloomer’s newspaper, The Lily, began in 1849 in Seneca Falls, New York, where Bloomer lived after her marriage. The newspaper was initially focused on temperance, but under the guidance of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, a contributor to the newspaper, the focus soon became the broad issues of women’s rights. An intriguing mix of contents ranging from recipes to moralist tracts, The Lily captivated readers from a broad spectrum of women and slowly educated them not only about the truth of women’s inequities but in the possibilities of major social reform. This first newspaper became a model for other suffrage periodicals that played a vital role in providing suffrage leaders and followers with a sense of community and continuity through the long years of the campaigns for the right to vote.

Bloomer was also known for her support for the outfit of tunic and full “pantelettes,” initially worn by actress Fanny Kemble and others, including Stanton. Bloomer defended the attire in The Lily, and her articles were picked up in The New York Tribune. Soon the outfit was known as “The Bloomer Costume,” even though Bloomer had no part in its creation. Ultimately Bloomer and other feminists abandoned the comfortable outfit, deciding that too much attention was centered on clothing instead of the issues at hand.

Bloomer remained a suffrage pioneer and writer throughout her life, leading suffrage campaigns in Nebraska and Iowa, as well as writing for a wide array of periodicals.

29 Oct

Overview of Transcendentalism

American Transcendentalism

Excerpted from: “Liquid Fire Within Me”: Language, Self and Society in Transcendentalism and early Evangelicalism, 1820-1860, M.A. Thesis in English by Ian Frederick Finseth, 1995.

THE EMERGENCE of the Transcendentalists as an identifiable movement took place during the late 1820s and 1830s, but the roots of their religious philosophy extended much farther back into American religious history. Transcendentalism and evangelical Protestantism followed separate evolutionary branches from American Puritanism, taking as their common ancestor the Calvinism of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Transcendentalism cannot be properly understood outside the context of Unitarianism, the dominant religion in Boston during the early nineteenth century. Unitarianism had developed during the late eighteenth century as a branch of the liberal wing of Christianity, which had separated from Orthodox Christianity during the First Great Awakening of the 1740s. That Awakening, along with its successor, revolved around the questions of divine election and original sin, and saw a brief period of revivalism. The Liberals tended to reject both the persistent Orthodox belief in inherent depravity and the emotionalism of the revivalists; on one side stood dogma, on the other stood pernicious “enthusiasm.” The Liberals, in a kind of amalgamation of Enlightenment principles with American Christianity, began to stress the value of intellectual reason as the path to divine wisdom. The Unitarians descended as the Boston contingent of this tradition, while making their own unique theological contribution in rejecting the doctrine of divine trinity.

Unitarians placed a premium on stability, harmony, rational thought, progressive morality, classical learning, and other hallmarks of Enlightenment Christianity. Instead of the dogma of Calvinism intended to compel obedience, the Unitarians offered a philosophy stressing the importance of voluntary ethical conduct and the ability of the intellect to discern what constituted ethical conduct. Theirs was a “natural theology” in which the individual could, through empirical investigation or the exercise of reason, discover the ordered and benevolent nature of the universe and of God’s laws. Divine “revelation,” which took its highest form in the Bible, was an external event or process that would confirm the findings of reason. William Ellery Channing, in his landmark sermon “Unitarian Christianity” (1819) sounded the characteristic theme of optimistic rationality:

Our leading principle in interpreting Scripture is this, that the Bible is a book written for men, in the language of men, and that its meaning is to be sought in the same manner as that of other books…. With these views of the Bible, we feel it our bounden duty to exercise our reason upon it perpetually, to compare, to infer, to look beyond the letter to the spirit, to seek in the nature of the subject, and the aim of the writer, his true meaning; and, in general, to make use of what is known, for explaining what is difficult, and for discovering new truths.

The intellectual marrow of Unitarianism had its counterbalance in a strain of sentimentalism: while the rational mind could light the way, the emotions provided the drive to translate ethical knowledge into ethical conduct. Still, the Unitarians deplored the kind of excessive emotionalism that took place at revivals, regarding it as a temporary burst of religious feeling that would soon dissipate. Since they conceived of revelation as an external favor granted by God to assure the mind of its spiritual progress, they doubted that inner “revelation” without prior conscious effort really represented a spiritual transformation.

Nonetheless, even in New England Evangelical Protestants were making many converts through their revivalist activities, especially in the 1820s and 1830s. The accelerating diversification of Boston increased the number of denominations that could compete for the loyalties of the population, even as urbanization and industrialization pushed many Bostonians in a secular direction. In an effort to become more relevant, and to instill their values of sobriety and order in a modernizing city, the Unitarians themselves adopted certain evangelical techniques. Through founding and participating in missionary and benevolent societies, they sought both to spread the Unitarian message and to bind people together in an increasingly fragmented social climate. Ezra Stiles Gannett, for example, a minister at the Federal Street Church, supplemented his regular pastoral duties with membership in the Colonization, Peace and Temperance societies, while Henry Ware Jr. helped found the Boston Philanthropic Society. Simultaneously, Unitarians tried to appeal more to the heart in their sermons, a trend reflected in the new Harvard professorship of Pastoral Theology and Pulpit Eloquence. Such Unitarian preachers as Joseph Stevens Buckminster and Edward Everett “set the model for a minister who could be literate rather than pedantic, who could quote poetry rather than eschatology, who could be a stylist and scorn controversy.” But they came nowhere near the emotionalism of the rural Evangelical Protestants. Unitarianism was a religion for upright, respectable, wealthy Boston citizens, not for the rough jostle of the streets or the backwoods. The liberalism Unitarians displayed in their embrace of Enlightenment philosophy was stabilized by a solid conservatism they retained in matters of social conduct and status.

During the first decade of the nineteenth century, Unitarians effectively captured Harvard with the election of Rev. Henry Ware Sr. as Hollis Professor of Divinity in 1805 and of Rev. John Thorton Kirkland as President in 1810. It was at Harvard that most of the younger generation of Transcendentalists received their education, and it was here that their rebellion against Unitarianism began. It would be misleading, however, to say that Transcendentalism entailed a rejection of Unitarianism; rather, it evolved almost as an organic consequence of its parent religion. By opening the door wide to the exercise of the intellect and free conscience, and encouraging the individual in his quest for divine meaning, Unitarians had unwittingly sowed the seeds of the Transcendentalist “revolt.”

The Transcendentalists felt that something was lacking in Unitarianism. Sobriety, mildness and calm rationalism failed to satisfy that side of the Transcendentalists which yearned for a more intense spiritual experience. The source of the discontent that prompted Emerson to renounce the “corpse-cold Unitarianism of Brattle Street and Harvard College” is suggested by the bland job description that Harvard issued for the new Professor of Natural Religion, Moral Philosophy and Civil Polity. The professor’s duties were to demonstrate the existence of a Deity or first cause, to prove and illustrate his essential attributes, both natural and moral; to evince and explain his providence and government, together with the doctrine of a future state of rewards and punishments; also to deduce and enforce the obligations which man is under to his Maker …. together with the most important duties of social life, resulting from the several relations which men mutually bear to each other; …. interspersing the whole with remarks, showing the coincidence between the doctrines of revelation and the dictates of reason in these important points; and lastly, notwithstanding this coincidence, to state the absolute necessity and vast utility of a divine revelation.

Perry Miller has argued persuasively that the Transcendentalists still retained in their characters certain vestiges of New England Puritanism, and that in their reaction against the “pale negations” of Unitarianism, they tapped into the grittier pietistic side of Calvinism in which New England culture had been steeped. The Calvinists, after all, conceived of their religion in part as man’s quest to discover his place in the divine scheme and the possibility of spiritual regeneration, and though their view of humanity was pessimistic to a high degree, their pietism could give rise to such early, heretical expressions of inner spirituality as those of the Quakers and Anne Hutchinson. Miller saw that the Unitarians acted as crucial intermediaries between the Calvinists and the Transcendentalists by abandoning the notion of original sin and human imperfectability:

The ecstasy and the vision which Calvinists knew only in the moment of vocation, the passing of which left them agonizingly aware of depravity and sin, could become the permanent joy of those who had put aside the conception of depravity, and the moments between could be filled no longer with self-accusation but with praise and wonder.

For the Transcendentalists, then, the critical realization, or conviction, was that finding God depended on neither orthodox creedalism nor the Unitarians’ sensible exercise of virtue, but on one’s inner striving toward spiritual communion with the divine spirit. From this wellspring of belief would flow all the rest of their religious philosophy.

Transcendentalism was not a purely native movement, however. The Transcendentalists received inspiration from overseas in the form of English and German romanticism, particularly the literature of Coleridge, Wordsworth and Goethe, and in the post-Kantian idealism of Thomas Carlyle and Victor Cousin. Under the influence of these writers (which was not a determinative influence, but rather an introduction to the cutting edge of Continental philosophy), the Transcendentalists developed their ideas of human “Reason,” or what we today would call intuition. For the Transcendentalists, as for the Romantics, subjective intuition was at least as reliable a source of truth as empirical investigation, which underlay both deism and the natural theology of the Unitarians. Kant had written skeptically of the ability of scientific methods to discover the true nature of the universe; now the rebels at Harvard college (the very institution which had exposed them to such modern notions!) would turn the ammunition against their elders. In an 1833 article in The Christian Examiner entitled simply “Coleridge,” Frederic Henry Hedge, once professor of logic at Harvard and now minister in West Cambridge, explained and defended the Romantic/Kantian philosophy, positing a correspondence between internal human reality and external spiritual reality. He wrote:

The method [of Kantian philosophy] is synthetical, proceeding from a given point, the lowest that can be found in our consciousness, and deducing from that point ‘the whole world of intelligences, with the whole system of their representations’ …. The last step in the process, the keystone of the fabric, is the deduction of time, space, and variety, or, in other words (as time, space, and variety include the elements of all empiric knowledge), the establishing of a coincidence between the facts of ordinary experience and those which we have discovered within ourselves ….

Although written in a highly intellectual style, as many of the Transcendentalist tracts were, Hedge’s argument was typical of the movement’s philosophical emphasis on non-rational, intuitive feeling. The role of the Continental Romantics in this regard was to provide the sort of intellectual validation we may suppose a fledgling movement of comparative youngsters would want in their rebellion against the Harvard establishment.

For Transcendentalism was entering theological realms which struck the elder generation of Unitarians as heretical apostasy or, at the very least, as ingratitude. The immediate controversy surrounded the question of miracles, or whether God communicated his existence to humanity through miracles as performed by Jesus Christ. The Transcendentalists thought, and declared, that this position alienated humanity from divinity. Emerson leveled the charge forcefully in his scandalous Divinity School Address (1838), asserting that “the word Miracle, as pronounced by Christian churches, gives a false impression; it is Monster. It is not one with the blowing clover and the falling rain.” The same year, in a bold critique of Harvard professor Andrews Norton’s magnum opus The Evidence of the Genuineness of the Four Gospels, Orestes Brownson identified what he regarded as the odious implications of the Unitarian position: “there is no revelation made from God to the human soul; we can know nothing of religion but what is taught us from abroad, by an individual raised up and specially endowed with wisdom from on high to be our instructor.” For Brownson and the other Transcendentalists, God displayed his presence in every aspect of the natural world, not just at isolated times. In a sharp rhetorical move, Brownson proceeded to identify the spirituality of the Transcendentalists with liberty and democracy:

…truth lights her torch in the inner temple of every man’s soul, whether patrician or plebeian, a shepherd or a philosopher, a Croesus or a beggar. It is only on the reality of this inner light, and on the fact, that it is universal, in all men, and in every man, that you can found a democracy, which shall have a firm basis, and which shall be able to survive the storms of human passions.

To Norton, such a rejection of the existence of divine miracles, and the assertion of an intuitive communion with God, amounted to a rejection of Christianity itself. In his reply to the Transcendentalists, “A Discourse on the Latest Form of Infidelity,” Norton wrote that their position “strikes at root of faith in Christianity,” and he reiterated the “orthodox” Unitarian belief that inner revelation was inherently unreliable and a potential lure away from the truths of religion.

The religion of which they speak, therefore, exists merely, if it exists at all, in undefined and unintelligible feelings, having reference perhaps to certain imaginations, the result of impressions communicated in childhood, or produced by the visible signs of religious belief existing around us, or awakened by the beautiful and magnificent spectacles which nature presents.

Despite its dismissive intent and tone, Norton’s blast against Transcendentalism is an excellent recapitulation of their religious philosophy. The crucial difference consisted in the respect accorded to “undefined and unintelligible feelings.”

The miracles controversy revealed how far removed the Harvard rebels had grown from their theological upbringing. It opened a window onto the fundamental dispute between the Transcendentalists and the Unitarians, which centered around the relationship between God, nature and humanity. The heresy of the Transcendentalists (for which the early Puritans had hanged people) was to countenance mysticism and pantheism, or the beliefs in the potential of the human mind to commune with God and in a God who is present in all of nature, rather than unequivocally distinct from it. Nevertheless, the Transcendentalists continued to think of themselves as Christians and to articulate their philosophy within a Christian theological framework, although some eventually moved past Christianity (as Emerson did in evolving his idea of an “oversoul”) or abandoned organized religion altogether.

Transcendentalists believed in a monistic universe, or one in which God is immanent in nature. The creation is an emanation of the creator; although a distinct entity, God is permanently and directly present in all things. Spirit and matter are perfectly fused, or “interpenetrate,” and differ not in essence but in degree. In such a pantheistic world, the objects of nature, including people, are all equally divine (hence Transcendentalism’s preoccupation with the details of nature, which seemed to encapsulate divine glory in microcosmic form). In a pantheistic and mystical world, one can experience direct contact with the divinity, then, during a walk in the woods, for instance, or through introspective contemplation. Similarly, one does not need to attribute the events of the natural world to “removed” spiritual causes because there is no such separation; all events are both material and spiritual; a miracle is indeed “one with the blowing clover and the falling rain.”

Transcendentalists, who never claimed enough members to become a significant religious movement, bequeathed an invaluable legacy to American literature and philosophy. As a distinct movement, Transcendentalism had disintegrated by the dawn of civil war; twenty years later its shining lights had all faded: George Ripley and Jones Very died in 1880, Emerson in 1882, Orestes Brownson in 1876, Bronson Alcott in 1888. The torch passed to those writers and thinkers who wrestled with the philosophy of their Transcendentalist forebears, keeping it alive in the mind more than in the church. At his one-hundredth lecture before the Concord Lyceum in 1880, Emerson looked back at the heyday of Transcendentalism and described it thus:

It seemed a war between intellect and affection; a crack in Nature, which split every church in Christendom into Papal and Protestant; Calvinism into Old and New schools; Quakerism into Old and New; brought new divisions in politics; as the new conscience touching temperance and slavery. The key to the period appeared to be that the mind had become aware of itself. Men grew reflective and intellectual. There was a new consciousness …. The modern mind believed that the nation existed for the individual, for the guardianship and education of every man. This idea, roughly written in revolutions and national movements, in the mind of the philosopher had far more precision; the individual is the world.

The Transcendentalists had stood at the vanguard of the “new consciousness” Emerson recalled so fondly, and it is for their intellectual and moral fervor that we remember them now as much as for their religious philosophy; the light of Transcendentalism today burns strongest on the page and in the classroom, rather than from the pulpit.

28 Oct

Thoreau quotes

Quotes from Henry David Thoreau

It is never too late to give up your prejudices. Walden

Why should we be in such desperate haste to succeed, and in such desperate enterprises? If a man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer. Walden

Rather than love, than money, than fame, give me truth. Walden

Some circumstantial evidence is very strong, as when you find a trout in the milk.

Most of the luxuries and many of the so-called comforts of life are not only not indispensable, but positive hindrances to the elevation of mankind. Walden

Things do not change; we change. Journal

In any weather, at any hour of the day or night, I have been anxious to improve the nick of time, and notch it on my stick too; to stand on the meeting of two eternities, the past and the future, which is precisely the present moment; to toe that line.

We do not enjoy poetry unless we know it to be poetry.

Beware of all enterprises that require new clothes.

So behave that the odor of your actions may enhance the general sweetness of the atmosphere, that when we behold or scent a flower, we may not be reminded how inconsistent your deeds are with it; for all odor is but one form of advertisement of a moral quality, and if fair actions had not been performed, the lily would not smell sweet. The foul slime stands for the sloth and vice of man, the decay of humanity; the fragrant flower that springs from it, for the purity and courage which are immortal.

For more than five years I maintained myself thus solely by the labour of my hands, and I found, that by working about six weeks in a year, I could meet all the expenses of living.

On tops of mountains, as everywhere to hopeful souls, it is always morning.

All this worldly wisdom was once the amiable heresy of some wise man. Journal

I heartily accept the motto, “That government is best which governs least”; and I should like to see it acted up to more rapidly and systematically. Civil Disobedience

Under a government which imprisons any unjustly, the true place for a just man is also a prison. Civil Disobedience

28 Oct

The Declaration of Sentiments

Women were prominent in many of the reform movements of the mid-19th century. They spoke out for abolitionism, for temperance, for humane treatment of the mentally ill, and for the right to education for all. The spirit of reform that swept America (and England) during the mid-19th century included the demand by some women that they be accorded complete legal and social equality. Leaders in the earliest days of this movement included Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Lucretia Mott.

The Seneca Falls Convention, held at Seneca Falls, New York July 19-20, 1848, was a culmination of women’s protest of their subordinate status as had been decried since Abigail Adams notoriously reminded her husband to “Remember the Ladies” while they were drafting a new government for the new American government. Three hundred men and women met during these two days to try to establish their case for women’s rights.

Questions to consider while reading:

1. What other document is echoed in the first few paragraphs of this one? Why do you think that is?

2. How was this convention received? Go to a report from the National Reformer newspaper and read the reaction of Gerrit Smith to the convention. Compare this to this article from the Oneida Whig newspaper.

3. Summarize the basic arguments against granting women equal rights, as listed in the article from the Oneida Whig above.

Declaration of Sentiments

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, July 19, 1848

When, in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one portion of the family of man to assume among the people of the earth a position different from that which they have hitherto occupied, but one to which the laws of nature and of nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes that impel them to such a course.

We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights governments are instituted, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. Whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of those who suffer from it to refuse allegiance to it, and to insist upon the institution of a new government, laying its foundation on such principles, and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness.

Prudence, indeed, will dictate that governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and, accordingly, all experience has shown that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they were accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same object, evinces a design to reduce them under absolute despotism, it is their duty to throw off such government and to provide new guards for their future security. Such has been the patient sufferance of the women under this government, and such is now the necessity which constrains them to demand the equal station to which they are entitled.

The history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman, having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her. To prove this, let facts be submitted to a candid world.

He has never permitted her to exercise her inalienable right to the elective franchise.

He has compelled her to submit to law in the formation of which she had no voice.

He has withheld from her rights which are given to the most ignorant and degraded men, both natives and foreigners.

Having deprived her of this first right as a citizen, the elective franchise, thereby leaving her without representation in the halls of legislation, he has oppressed her on all sides.

He has made her, if married, in the eye of the law, civilly dead.

He has taken from her all right in property, even to the wages she earns.

He has made her morally, an irresponsible being, as she can commit many crimes with impunity, provided they be done in the presence of her husband. In the covenant of marriage, she is compelled to promise obedience to her husband, he becoming, to all intents and purposes, her master — the law giving him power to deprive her of her liberty and to administer chastisement.

He has so framed the laws of divorce, as to what shall be the proper causes and, in case of separation, to whom the guardianship of the children shall be given, as to be wholly regardless of the happiness of the women — the law, in all cases, going upon a false supposition of the supremacy of man and giving all power into his hands.

After depriving her of all rights as a married woman, if single and the owner of property, he has taxed her to support a government which recognizes her only when her property can be made profitable to it.

He has monopolized nearly all the profitable employments, and from those she is permitted to follow, she receives but a scanty remuneration. He closes against her all the avenues to wealth and distinction which he considers most honorable to himself. As a teacher of theology, medicine, or law, she is not known.

He has denied her the facilities for obtaining a thorough education, all colleges being closed against her.

He allows her in church, as well as state, but a subordinate position, claiming apostolic authority for her exclusion from the ministry, and, with some exceptions, from any public participation in the affairs of the church.

He has created a false public sentiment by giving to the world a different code of morals for men and women, by which moral delinquencies which exclude women from society are not only tolerated but deemed of little account in man.

He has usurped the prerogative of Jehovah himself, claiming it as his right to assign for her a sphere of action, when that belongs to her conscience and to her God.

He has endeavored, in every way that he could, to destroy her confidence in her own powers, to lessen her self-respect, and to make her willing to lead a dependent and abject life.

Now, in view of this entire disfranchisement of one-half the people of this country, their social and religious degradation, in view of the unjust laws above mentioned, and because women do feel themselves aggrieved, oppressed, and fraudulently deprived of their most sacred rights, we insist that they have immediate admission to all the rights and privileges which belong to them as citizens of the United States.

In entering upon the great work before us, we anticipate no small amount of misconception, misrepresentation, and ridicule; but we shall use every instrumentality within our power to effect our object. We shall employ agents, circulate tracts, petition the state and national legislatures, and endeavor to enlist the pulpit and the press in our behalf. We hope this Convention will be followed by a series of conventions embracing every part of the country.

Resolutions

Whereas, the great precept of nature is conceded to be that “man shall pursue his own true and substantial happiness.” Blackstone in his Commentaries remarks that this law of nature, being coeval with mankind and dictated by God himself, is, of course, superior in obligation to any other. It is binding over all the globe, in all countries and at all times; no human laws are of any validity if contrary to this, and such of them as are valid derive all their force, and all their validity, and all their authority, mediately and immediately, from this original; therefore,

Resolved, That such laws as conflict, in any way, with the true and substantial happiness of woman, are contrary to the great precept of nature and of no validity, for this is “superior in obligation to any other.”

Resolved, that all laws which prevent woman from occupying such a station in society as her conscience shall dictate, or which place her in a position inferior to that of man, are contrary to the great precept of nature and therefore of no force or authority.

Resolved, that woman is man’s equal, was intended to be so by the Creator, and the highest good of the race demands that she should be recognized as such.

Resolved, that the women of this country ought to be enlightened in regard to the laws under which they live, that they may no longer publish their degradation by declaring themselves satisfied with their present position, nor their ignorance, by asserting that they have all the rights they want.

Resolved, that inasmuch as man, while claiming for himself intellectual superiority, does accord to woman moral superiority, it is preeminently his duty to encourage her to speak and teach, as she has an opportunity, in all religious assemblies.

Resolved, that the same amount of virtue, delicacy, and refinement of behavior that is required of woman in the social state also be required of man, and the same transgressions should be visited with equal severity on both man and woman.

Resolved, that the objection of indelicacy and impropriety, which is so often brought against woman when she addresses a public audience, comes with a very ill grace from those who encourage, by their attendance, her appearance on the stage, in the concert, or in feats of the circus.

Resolved, that woman has too long rested satisfied in the circumscribed limits which corrupt customs and a perverted application of the Scriptures have marked out for her, and that it is time she should move in the enlarged sphere which her great Creator has assigned her.

Resolved, that it is the duty of the women of this country to secure to themselves their sacred right to the elective franchise.

Resolved, that the equality of human rights results necessarily from the fact of the identity of the race in capabilities and responsibilities.

Resolved, that the speedy success of our cause depends upon the zealous and untiring efforts of both men and women for the overthrow of the monopoly of the pulpit, and for the securing to woman an equal participation with men in the various trades, professions, and commerce.

Resolved, therefore, that, being invested by the Creator with the same capabilities and same consciousness of responsibility for their exercise, it is demonstrably the right and duty of woman, equally with man, to promote every righteous cause by every righteous means; and especially in regard to the great subjects of morals and religion, it is self-evidently her right to participate with her brother in teaching them, both in private and in public, by writing and by speaking, by any instrumentalities proper to be used, and in any assemblies proper to be held; and this being a self-evident truth growing out of the divinely implanted principles of human nature, any custom or authority adverse to it, whether modern or wearing the hoary sanction of antiquity, is to be regarded as a self-evident falsehood, and at war with mankind.

Links for More Information:

The Seneca Falls Convention

The Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony Papers Project

Exhibit on the Seneca Falls Convention from the Library of Congress

Vocabulary for this post:

prudence

transient

usurpations

evinces

franchise

impunity

chastisement

apostolic

coeval

21 Oct

Chapter 15 questions

Chapter 15 Questions

Remember to answer in your own handwriting, in your own words, and fully and completely.

1. What were the three revolutions that took place in America during the first half of the 19th century, according to your text? What were the characteristics of the “third revolution?”

2. Explain how American religious practices changed during this time period, including explanation of Deism and Unitarianism. How had common religious beliefs changed since the time of the Puritans, especially in terms of diversity?

3. What were the main causes and characteristics of the Second Great Awakening? How did revivalists such as Charles G. Finney influence American religious practice? How did the 2nd Great awakening reshape American religion? Which denominations gained the most membership, and how did class and region play an influence?

4. What were some uniquely American religions that began during this time period? Explain their main beliefs and founders? What link is there to the current presidential election? What did William Miller believe?

5. Why were Mormons often viewed with suspicion by their neighbors?

6. How was education impacted by the 2nd Great Awakening? How did a Webster make a difference? Consider both elementary and collegiate education. How were women impacted?

7. What is the difference between temperance and prohibition (look it up)? What factors led to drives to ban alcohol, and where and when were these drives successful? What organizations sought to limit alcohol consumption?

8. How and why were women involved in these reform movements, and how did their participation echo traditional women’s concerns? What did Dorothea Dix work to reform? In what two areas were women thought to be superior to men? What about rape laws in the US? What reform movement eclipsed the emphasis on women’s rights?

9. What were the main beliefs of the communal living movements? Make a chart outlining some of the main groups, their founders, and their characteristics. Were any of these groups successful? Explain. Which one was the weirdest in your opinion, and why?

10. What changes took place in American medicine during this time (including regarding mental health)? What scientific and philosophical achievements took place during this time?

11. What uniquely American artistic movements were there, and what were they trying to express? Who was the one influential southern writer? Why is Poe different than most of these other writers?

12. Explain the main writers and beliefs of the transcendentalist movement? Was it rationalist? Explain. What were the main points of “On Civil Disobedience” and “Self-Reliance”? What utopian movement was associated with transcendentalism?

13. How did the rising nationalism after 1812 affect American arts and letters (writers)?

You must be logged in to post a comment.