Go here: http://voices.yahoo.com/monsieur-batignole-wonderful-film-holocaust-77038.html

Archive for the ‘Class discussion’ Category

13 Feb

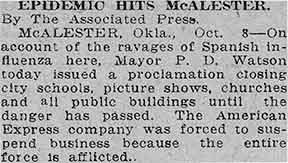

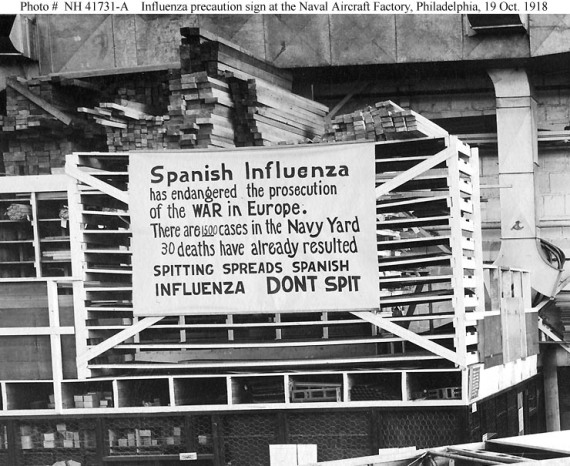

The 1918 Influenza Pandemic

This site has a nice overview of the flu outbreak worldwide:

http://virus.stanford.edu/uda/

Then make sure that you read this article from the New York Times, which mentions how St. Louis’s response was much wiser than Philadelphia’s:

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/17/health/17flu.html

And here is the short article by Tim O-Neill from the Post-Dispatch, which I will just copy here because they never keep their links current:

ST. LOUIS – In October 1918, the meat grinder known as World War I was lurching to its exhausted conclusion in the Argonne forest. Another, even bigger, killer was just getting started.

The 1918-19 influenza pandemic, known to history as the Spanish flu, was racing across the world. Estimates of the flu’s worldwide toll range from 25 million to 50 million deaths, including 675,000 in the U.S. The numbers overwhelmed the butchery of four years of ghastly trench war, which managed to kill about 8.6 million, including 116,000 American doughboys.

In St. Louis, a strong-willed doctor moved quickly, drastically and successfully to limit the horror. He was Dr. Max C. Starkloff, then in the 15th of his 30 years as city health commissioner. He prevailed on Mayor Henry Kiel to let him order the closing of almost all public places, including churches, schools, dance halls, fraternal lodges, theaters – even open-air funerals. His proclamation said that “Spanish flu is now present and probably will become epidemic in St. Louis.”

The Liberty Loan Organization canceled its rallies. Washington University football players wore masks in practice. St. Louis police officers were told to forgo arrests on petty cases, the better to reduce court docket calls.

Starkloff issued his order on Oct. 7, 1918, only three days after the first reported case of influenza in the city. But there already had been two flu deaths among the soldiers just south of the city at Jefferson Barracks, where the hospital population was 800 and growing quickly.

Starkloff’s strategy was “social distancing,” the simple practice of keeping people away from one another. During the brief but deadly sweep of the flu that fall, the death rate in St. Louis was 2.8 per 1,000 residents, lowest among the nation’s major cities. The rate was 8.0 in Pittsburgh, 7.6 in San Francisco and 7.1 in Kansas City.

Businessmen whose sales plunged beseeched City Hall to loosen the rules. Catholic Archbishop (later Cardinal) John J. Glennon urged Starkloff to reopen the churches. But the son of a German-born doctor held firm and had the trust of Mayor Kiel, who told Starkloff, “I don’t want anyone to die. Therefore, I shall support you.”

On Nov. 11, Armistice Day, Starkloff let downtown stores sell American flags, but only outside on the sidewalks. He allowed the schools to reopen a few days later and lifted the last of his ban on Nov. 18. Near month’s end, Starkloff closed the schools again for a short time.

Deaths continued, even spiking in December. But the number of new cases fell. The virus worked quickly through its victims, then faded. It had infected 31,500 people in St. Louis and killed 1,703.

Starkloff retired in 1933 and died at home in Carondelet in 1942 at age 82. Shortly after his death, a grateful city renamed its City Hospital just south of downtown in memory of him. One of his great-grandchildren is Max Starkloff, a local leader in disability services who founded Paraquad Inc. and the Starkloff Disability Institute.

14 Jan

Links for Industrialization and Urbanization

Bobbin boys and other child laborers: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bobbin_boy

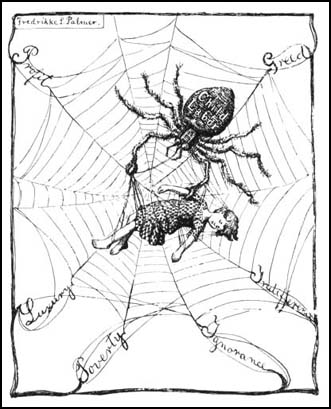

Cartoon about child labor:

The Great Chicago Fire and its impact: http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h1854.html

Jane Addams and Hull House: http://www.hullhouse.org/aboutus/history.html

Grace Hill Settlement House in St. Louis: http://www.gracehill.org/content/history.php

The Carnegie Corporation: http://carnegie.org/ Hold your pointer over the programs menu to see all the different aims of this 100 year old philanthropic foundation.

13 Jan

Link to Gospel of Wealth excerpt and notes to take….

These questions will be due on Wednesday/Thursday.

Go here (http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/1889carnegie.html).

You can also go here, and actually hear Carnegie read an excerpt himself: http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5766

1. Would Carnegie’s employees agree with the means he used to amass his wealth??

2. What did he list as the three things a millionaire could do with his or her fortune?

3. Why is the first option not a good idea? (Consider Paris Hilton…)

4. Why was Carnegie in favor of a high estate tax (which he called a “death tax”)?

5. What did Carnegie end up doing with his wealth?

6. Why can it be argued that Carnegie’s attitude is paternalistic?

2 Dec

Ex parte Merryman and Ex parte Milligan

Be able to discuss with me: was the Lincoln administration and the Union army right in holding John Merryman or Lambdin Milligan (what an unfortunate name!)?

Here is a nice summary from PBS regarding Ex parte Milligan: http://www.pbs.org/wnet/supremecourt/antebellum/landmark_exparte.html

Here is a great discussion of the problem of habeas corpus in wartime in general: http://www.etymonline.com/cw/habeas.htm . This provides the background info to the case of John Merryman and Lambdin Milligan.

Excerpts from the decision of Ex parte Merryman (having to do with the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus by Chief Justice Taney:

“…The case, then, is simply this: A military officer residing in Pennsylvania issues an order to arrest a citizen of Maryland, upon vague and indefinite charges, without any proof, so far as appears. Under this order his house is entered in the night; he is seized as a prisoner, and conveyed to Fort McHenry, and there kept in close confinement. And when a habeas corpus is served on the commanding officer, requiring him to produce the prisoner before a Justice of the Supreme Court, in order that he may examine into the legality of the imprisonment, the answer of the officer is that he is authorized by the President to suspend the writ of habeas corpus at his discretion, and, in the exercise of that discretion, suspends it in this case, and on that ground refuses obedience to the writ.

As the case comes before me, therefore, I understand that the President not only claims the right to suspend the writ of habeas corpus himself, at his discretion, but to delegate that discretionary power to a military officer, and to leave it to him to determine whether he will or will not obey judicial process that may be served upon him.

No official notice has been given to the courts of justice, or to the public, by proclamation or otherwise, that the President claimed this power, and had exercised it in the manner stated in the return. And I certainly listened to it with some surprise, for I had supposed it to be one of those points of constitutional law upon which there is no difference of opinion, and that it was admitted on all hands that the privilege of the writ could not be suspended except by act of Congress….

The clause in the Constitution which authorizes the suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus is in the ninth section of the first article.

This article is devoted to the Legislative Department of the United States, and has not the slightest reference to the Executive Department….

But the documents before me show that the military authority in this case has gone far beyond the mere suspension of the privilege of the writ ofhabeas corpus. It has, by force of arms, thrust aside the judicial authorities and officers to whom the Constitution has confided the power and duty of interpreting and administering the laws, and substituted a military government in its place, to be administered and executed by military officers. For at the time these proceedings were had against John Merryman, the District Judge of Maryland–the commissioner appointed under the act of Congress–the District Attorney and the Marshal, all resided in the city of Baltimore, a few miles only from the home of the prisoner. Up to that time there had never been the slightest resistance or obstruction to the process of any Court or judicial officer of the United States in Maryland, except by the military authority. And if a military officer, or any other person, had reason to believe that the prisoner had committed any offence against the laws of the United States, it was his duty to give information of the fact and the evidence to support it to the District Attorney, and it would then have become the duty of that officer to bring the matter before the District Judge or Commissioner, and if there was sufficient legal evidence to justify his arrest, the Judge or Commissioner would have issued his warrant to the Marshal to arrest him, and, upon the hearing of the party, would have held him to bail, or committed him for trial, according to the character of the offense as it appeared in the testimony, or would have discharged him immediately if there was not sufficient evidence to support the accusation. There was no danger of any obstruction or resistance to the action of the civil authorities, and therefore no reason whatever for the interposition of the military. And yet, under these circumstances, a military officer, stationed in Pennsylvania, without giving any information to the District Attorney, and without any application to the judicial authorities, assumes to himself the judicial power in the District of Maryland; undertakes to decide what constitutes the crime of treason or rebellion; what evidence (if, indeed, he required any) is sufficient to support the accusation and justify the commitment; and commits the party, without having a hearing even before himself, to close custody in a strongly garrisoned fort, to be there held, it would seem, during the pleasure of those who committed him.

The Constitution provides, as I have before said, that “no person shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” It declares that “the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects against unreasonable searches and seizures shall not be violated, and no warrant shall issue but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched and the persons or things to be seized.” It provides that the party accused shall be entitled to a speedy trial in a court of justice.

And these great and fundamental laws, which Congress itself could not suspend, have been disregarded and suspended, like the writ of habeas corpus, by a military order, supported by force of arms. Such is the case now before me; and I can only say that if the authority which the Constitution has confided to the judiciary department and judicial officers may thus upon any pretext or under any circumstances be usurped by the military power at its discretion, the people of the United States are no longer living under a Government of laws, but every citizen holds life, liberty, and property at the will and pleasure of the army officer in whose military district he may happen to be found….”

Full text of Taney’s decision here: http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=442 He even brings up Aaron Burr!

26 Aug

Overview: The First Great Awakening

The roots of the Great Awakening of the early 18th century lie in several places, not the least of which was the challenge that the Enlightenment posed to religious faith. Although the revivalism of the Great Awakening influenced England and all the American colonies, we will focus here on how the religious movement unfolded in New England. There, the Puritans were at the same time experiencing internal stresses as the number of people who met the requirements for church membership dwindled. Enlightenment thought challenged common assumptions and inverted the traditional primacy of faith over reason. The Great Awakening was a reaction to these challenges.

The scientific movement known as the Enlightenment spread from Europe to America. Common names associated with this time of flowering rationalism include Sir Isaac Newton and John Locke. Newton’s theories about the laws that governed the motions of celestial bodies showed that the tracks the stars and planets traced through the sky were predictable and could be understood by humans. Likewise, Locke, in his Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690) argued that children were not born with innate knowledge planted in them by God, but were instead capable of reasoning and gaining knowledge by experience, which contradicted the prevailing view of many. Locke and other Enlightenment thinkers believed that people were capable of great progress and of improving the conditions in which they lived, especially through science and reasoning. This challenged the foundations of ideas like predestination, for the idea that one can change and improve the conditions of life implied that God had not created humans as cogs in a machine, but as active players in the universe. However, neither man challenged the existence of God. There was room for faith in a world of reason.

One attempt to reconcile faith and reason was called Christian rationalism, which stressed that humans were born with free will and through moral, rational behavior they could gain salvation. The rationalists accepted all into church membership who were trying to live Christian lives, instead of merely the “visible saints.” Thus rationalism directly challenged the core beliefs of Calvinism, especially predestination. Instead, some rationalist Puritans began espousing a belief in Arminianism, that humans had the freedom to choose salvation through good works and faith. Arminianism dovetailed very well with Enlightenment thought about how humans were free to influence their own destinies. Rationalists believed that salvation could be gained through actions, not just as a capricious gift from God. Traditionalists, of course, rejected these ideas as heretical. Arminianism became an influential theory in the early 18th century at Harvard College, which served as a training ground for Congregationalist ministers. The new generation of Puritan ministers began assuming leadership roles in the Congregationalist churches of New England. Thus, a tension between these two opposing factions caused great unrest among Christians in America.

Further complicating matters was the fact that the Puritans had experienced a serious reduction in membership. Since about 1650, membership had declined, especially among men, whom some ministers accused of being too worldly. Women definitely seemed to have an advantage in exhibiting what was called ‘regeneration’ after a believable conversion experience. In some congregations, women made up sixty to seventy-five percent of new members. In 1662, the Puritan clergy created the Half-Way Covenant, which allowed adults who had been baptized as children but not yet saved “half-way” membership. These members could not take communion, but could have their children baptized as long as they demonstrated understanding of Christian beliefs and lived in obedience to God’s laws. On a practical note, the Half-Way Covenant was also an attempt to keep influential people within the Puritan faith, for no matter how strictly the Puritans had attempted to wipe out dissenters and other denominations, the Puritans now faced competition from Baptists and Quakers, among others. But the Half-Way Covenant was not accepted by all congregations, and thus caused more dissension rather than growth.

The increasing stratification within society also affected the discontent felt by many within the second generation of Puritans. As the older generation increasingly concentrated upon attaining wealth, some churches also allowed a differentiation within the sanctuary itself, as wealthy families were given prominent pews within the church during services (during the early years of settlement in America, it was a common practice for a family to subscribe for a pew, thereby paying for the privilege of one’s seat). Naturally, some of the younger, less wealthy Puritans felt further estrangement, and soon stopped attending services. The Rev. Jonathan Edwards of Northampton, Massachusetts focused his attention upon this disaffected generation. He tried to reawaken their piety by appealing to their emotions in a series of sermons that sought to impel his congregants to examine their lives, come to grips with their fate as sinners unless saved by God. This appeal to emotionalism worked, and people felt reconnected to their faith. Soon Edward’s congregation was growing in membership. Revivals of religious feeling were also sweeping through the Methodist and Presbyterian churches in the colonies.

This effort by Edwards marked the beginning of the Great Awakening in New England. Into this time of crisis burst a new attempt to revive religious enthusiasm: the First Great Awakening, which erupted in New England between the years of 1734 and 1745. Those who supported the ideals of the Great Awakening became known as New Lights; traditionalists were called Old Lights.

There were several identifying features of this movement. New Light pastors thundered from their pulpits. Itinerant preachers roamed the countryside, sometimes speaking from the pulpits of churches they visited, but also drawing large crowds in fields or on the steps of meetinghouses. From 1739 to 1741, the youthful Rev. George Whitefield, an Anglican evangelist from England, toured around the Middle Colonies, and several of his sermons were printed by his friend Benjamin Franklin, who was known as a religious skeptic. He was invited to preach in the Connecticut River Valley by Jonathan Edwards, and from there he moved through New England preaching in various places to enthusiastic reviews. Crowds as large as 8,000 listened to him preach in Boston. Instead of dry, reasoned sermons, listeners were painted vivid pictures of the fires of hell in highly emotional language. Audiences often responded in kind, being driven to shrieks of horror, panic, and tears. People grew pale and sometimes collapsed in the arms of their loved ones; others cried out to God for mercy in the middle of a service. Those who experienced this step often moved to a state of euphoria as the last phase of their reawakening, as the feeling of God’s salvation gathered within their hearts and overwhelmed them.

Soon these different approaches to religious feeling flared into open confrontation. An implicit thread running through New Light sermons was criticism of mainline Protestantism as being spiritually dead and decadent. Clergy became subject to criticism and dismissal. Some churches broke into factions or split along doctrinal lines. In one congregation, the minister was asked to step down because he lacked the emotional fire his awakened congregants wanted. When he refused, he was pulled from the pulpit, assaulted, and thrown out the door of the church. . Ideas about education were also affected by this criticism of the “spiritual coldness” of unconverted ministers. A Presbyterian minister, William Tennent, established a school in New Jersey to train preachers in the New Light methods and theology. Originally called the “Log College,” this school was later christened the College of New Jersey and is today known as Princeton. Tennent’s son Gilbert Tennent became an influential New Light preacher.

These Presbyterian graduates of the Log College were soon making their way down the coastline to the southern colonies. By the 1740s, the revival had spread to the southern colonies, carried by William Tennent’s troops. Methodists and Baptists also reaped a windfall of converts, and during the Awakening in this era, many slaves were exposed to Christianity for the first time. Some churches even had both black and white members for a time. For the next twenty years, revivalism played a strong part in the religious experiences of many Southerners.

The Great Awakening also had political and educational consequences. Some Old Lights, particularly in New England, attempted to pass laws to quell the influence of the New Lights. This religious division had political consequences in New England, since the church and government were so tightly intertwined. The Connecticut Assembly passed a law forbidding a clergyman to preach from another’s pulpit without permission and repealed toleration laws passed in 1708. This heavy-handedness ultimately created a backlash in support of religious freedom that would resonate even to the present day. Higher education in the colonies benefitted from this religious revival. Besides Princeton, several colleges sprung up during this time, including Brown, Rutgers, and Dartmouth, for the purpose of meeting the increased need for preachers. These institutions introduced a new curriculum that emphasized mathematics, science, and modern languages in addition to the classical studies and theology which had prevailed previously in older schools. Students at Yale who were swayed by New Light theology began stirring up so much unrest that the Connecticut Assembly allowed expulsion for any student who attended New Light services. The Great Awakening pitted the New Lights’ call for a return to Calvinism against the Old Lights’ more liberal tendencies, which would eventually lead to the founding of the Unitarian and Universalist churches.

To this day, a split remains within American Protestantism, a split that was first articulated during the First Great Awakening. The Christian Charismatic movement, which emphasizes emotion, spiritual gifts such as prophecy, and shattering conversion experiences, still dominates some denominations, such as the Assembly of God based in Springfield, Missouri, as well as the work of evangelists such as Billy and Franklin Graham. The Great Awakening encouraged democratic tendencies and also promoted the separation of church and state, since New Lights were rebelling against the control Old Lights were able to wield through the administration of anti-revivalist laws. Although the religious fervor that was encouraged by the Great Awakening has experienced varying levels of influence throughout American history up to the present, the dichotomy between faith and reason has never completely subsided from the American social landscape.

25 Apr

Civil Liberties in Times of Emergency

With the capture and arrest of the suspect in the Boston Marathon bombings, there are three opinion pieces I want you to read, as well as the first three paragraphs in particular from the front page of Thursday’s paper. As you hopefully know, at first authorities considered charging the surviving bomber as an enemy combatant, and deliberately decided not to Mirandize him once he regained consciousness. Remember that he is a naturalized US citizen captured on American soil and has so far not been tied to any international terrorist organizations.

http://www.stltoday.com/news/national/boston-bomb-investigation-extends-to-russia/article_047ec30a-d724-5b49-9811-c4c0941fd3dc.html (first three paragraphs are particularly important).

First, from an editorial from the Post-Dispatch: http://www.stltoday.com/news/opinion/columns/the-platform/editorial-president-or-terror-suspect-the-rule-of-law-applies/article_411048ff-1e15-5032-8b1c-9756bc4a7d93.html

And this one from conservative commentator George Will: http://www.stltoday.com/news/opinion/columns/george-will/george-will-the-shame-of-deference/article_20bdbf54-e3fd-5fdb-aab5-7d8bb93e623e.html

And from moderate Kathleen Parker: http://www.stltoday.com/news/opinion/columns/kathleen-parker/kathleen-parker-the-terror-of-not-knowing/article_033f880d-56ef-5535-b1c5-0b7df2d2b74b.html

This is a great chance to APPLY what we learn and use it to determine our course of action. It is also a good chance to review the Constitutional Amendments and Supreme Court decisions as well as other historical precedents that apply to our understanding of civil liberties. We will be discussing this in class next Tuesday, April 30. Take notes and CONSIDER your answer to these questions:

What are civil liberties? What is the purpose of civil liberties? Are they negotiable or variable? What does history show us about limitations on civil liberties in times of war or crisis? What points does George Will make about previous instances of racially-based civil liberties decisions? What point does Kathleen Parker make about the ease of stripping those perceived as “alien” or “other” of their rights and claims to humanity?

Here is a link outlining very briefly the current case law on the matter of enemy combatants and civil liberties: http://web.law.duke.edu/publiclaw/civil/index.php?action=showtopic&topicid=24

8 Dec

Links to article from this week’s discussion on citizenship

Maryland Heights woman tries to prove her US citizenship: http://www.stltoday.com/news/local/metro/woman-fights-to-prove-she-s-a-u-s-citizen/article_beba66e5-a28d-5691-88a7-bc1c16ad66af.html

Legal definition of Jus soli: http://definitions.uslegal.com/j/jus-soli/

Legal definition of Jus sanguinis: http://definitions.uslegal.com/j/jus-sanguinis/

Here’s a story of widowed spouses facing deportation: http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/30056223/ns/us_news-life/t/widowed-immigrants-fight-deportation/

Some politicians have called for the 14th Amendment to be revised:

http://www.postandcourier.com/news/2010/aug/08/14th-amendment-revision-push-stalls/

28 Nov

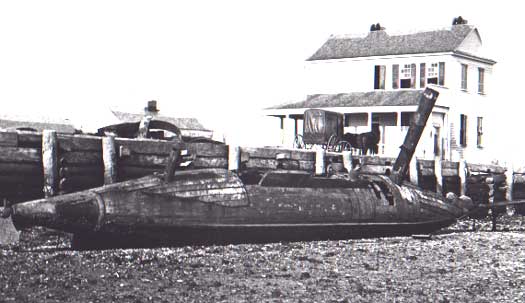

Submarine warfare in the Civil War: the CSS Hunley

The first submarine ever used in warfare was named The Turtle, appropriately enough. Take a guess when it was used– would you say 1914, or 1899 or even 1864? You would be wrong.

The Turtle was a one-man- human powered sub– used against the British in 1776. It was designed by American David Bushnell during the Revolutionary War. It failed to damage any British ships, but it made the British a lot more vigilant about security for their ships.

Robert Fulton, of steamboat fame, built a submarine named the Nautilus in France in 1801. It even had a sail for propulsion when it was on the surface.

The Confederate States of America first tried to use a submarine-like ship when it lauched the David in 1862. Its smokestack and breathing tube stuck up above the waterline, so it wasn’t completely submersed, but it was close to being a submarine. It used a spar torpedo (an explosive charge attached to a pole on the bow of the vessel) to punch a hole in a Union ironclad, but the ship did not sink. The Confederacy built 20 more Davids, but none of them managed actually to sink an enemy ship.

Click on the above black box to see an artist’s rendering of the Hunley.

So along came the Hunley. Forty feet long and only 4 feet wide, it was a converted boiler. It carried a nine man crew, and eight of them turned a crankshaft to propel the ship forward. The goal was to implant the explosive canister from a spar torpedo again. Yet this was a very dangerous assignment. The men sat hunched over in the darkness, their only light a candle– which also would warn them that their oxygen was depleted when it sputtered out. Several crews died, but eventually, on July 17, 1864, the Hunley sank the USS Housatonic near Charleston harbor. But the sub and its crew were never seen again.

The sub, in fact, was lost completely, until it was discovered by divers in 1995. In 2000, it was carefully brought to the surface. The remains of its crew were examined and later laid to rest. The Hunley is now being restored so that it can go on permanent display.

The Union made its own sub, name the Intelligent Whale, but it was never used in battle. They also bought a sub from the French, the Alligator, but it was lost at sea in 1862. Submarines would not be used again in battle by Americans until the 20th century.

Links for further information:

David Bushnell and the first American submarine

Who were the crew of the Hunley?

Civil War submarines

20 Nov

Links on the election of 1860 and the Crittenden Compromise

The election of 1860, from nominating conventions to results: http://elections.harpweek.com/1860/overview-1860-1.htm

The Crittenden Compromise: http://sunsite.utk.edu/civil-war/critten.html

You must be logged in to post a comment.