Remember, never never NEVER run in front of a cannon. You will become very hole-y.

Archive for the ‘Chapter 21’ Category

5 Dec

Pickett’s Charge– the End

3 Dec

The Anaconda Plan

General Winfield Scott, commander of the U.S. Army, sent this letter to George McClellan during the earliest stages of the war. It was in reply to a letter from McClellan which set forth several proposals for the prosecution of the war. In this reply Scott gives his ideas on the subject, which were to become known as the Anaconda Plan.

As you read, consider the following questions:

1. summarize the major characteristics of the Anaconda Plan.

2. What does Scott say about giving the 90-day volunteers the best weaponry? Why would he say this?

HEADQUARTERS OF THE ARMY,

Washington, May 3, 1861.

Maj. Gen. GEORGE B. MCCLELLAN,

Commanding Ohio Volunteers, Cincinnati, Ohio:

SIR: I have read and carefully considered your plan for a campaign, and now send you confidentially my own views, supported by certain facts of which you should be advised.

First. It is the design of the Government to raise 25,000 additional regular troops, and 60,000 volunteers for three years. It will be inexpedient either to rely on the three-months’ volunteers for extensive operations or to put in their hands the best class of arms we have in store. The term of service would expire by the commencement of a regular campaign, and the arms not lost be returned mostly in a damaged condition. Hence I must strongly urge upon you to confine yourself strictly to the quota of three-months’ men called for by the War Department.

Second. We rely greatly on the sure operation of a complete blockade of the Atlantic and Gulf ports soon to commence. In connection with such blockade we propose a powerful movement down the Mississippi to the ocean, with a cordon of posts at proper points, and the capture of Forts Jackson and Saint Philip; the object being to clear out and keep open this great line of communication in connection with the strict blockade of the seaboard, so as to envelop the insurgent States and bring them to terms with less bloodshed than by any other plan. I suppose there will be needed from twelve to twenty steam gun-boats, and a sufficient number of steam transports (say forty) to carry all the personnel (say 60,000 men) and material of the expedition; most of the gunboats to be in advance to open the way, and the remainder to follow and protect the rear of the expedition, &c. This army, in which it is not improbable you may be invited to take an important part, should be composed of our best regulars for the advance and of three-years’ volunteers, all well officered, and with four months and a half of instruction in camps prior to (say) November 10. In the progress down the river all the enemy’s batteries on its banks we of course would turn and capture, leaving a sufficient number of posts with complete garrisons to keep the river open behind the expedition. Finally, it will be necessary that New Orleans should be strongly occupied and securely held until the present difficulties are composed.

Third. A word now as to the greatest obstacle in the way of this plan–the great danger now pressing upon us – the impatience of our patriotic and loyal Union friends. They will urge instant and vigorous action, regardless, I fear, of consequences – that is, unwilling to wait for the slow instruction of (say) twelve or fifteen camps, for the rise of rivers, and the return of frosts to kill the virus of malignant fevers below Memphis. I fear this; but impress right views, on every proper occasion, upon the brave men who are hastening to the support of their Government. Lose no time, while necessary preparations for the great expedition are in progress, in organizing, drilling, and disciplining your three-months’ men, many of whom, it is hoped, will be ultimately found enrolled under the call for three-years’ volunteers. Should an urgent and immediate occasion arise meantime for their services, they will be the more effective. I commend these views to your consideration, and shall be happy to hear the result.

With great respect, yours, truly,

WINFIELD SCOTT.

3 Dec

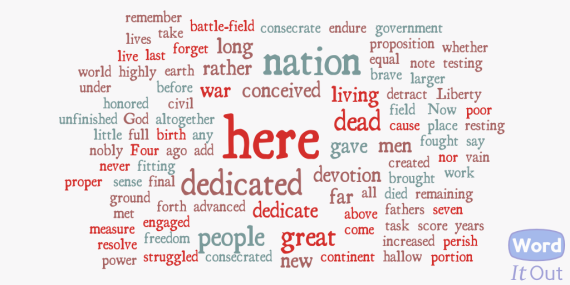

The Gettysburg Address

Given November 19, 1863

“Fourscore and seven years ago

our fathers brought forth upon this continent

a new nation

conceived in liberty

and dedicated to the proposition

that all men are created equal.

“Now we are engaged in a great civil war,

testing whether this nation

or any nation so conceived and so dedicated

can long endure.

We are met on a great battlefield of that war.

We have come to dedicate a portion of that field

as a final resting-place for those who here gave their lives

that that nation might live.

It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

“But in a larger sense,

we cannot dedicate,

we cannot consecrate,

we cannot hallow this ground.

The brave men, living and dead who struggled here

have dedicated it far above our poor power to add or detract.

The world will little note nor long remember what we say here,

but it can never forget what they did here.

It is for us

the living

rather to be dedicated here to the unfinished work

which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced.

It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us–

that from these honored dead we take increased devotion

to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion–

that we here highly resolve

that these dead shall not have died in vain,

that this nation under God shall have a new birth of freedom,

and that government

of the people,

by the people,

and for the people

shall not perish from the earth.”

3 Dec

Antietam photograph and Matthew Brady’s other work

watch?v=FNt9PJMzcn4&feature=related]

watch?v=GtgzG1kqaY0&feature=related]

Matthew Brady is referred to here as “The Father of Photojournalism.” His work was controversial because it was so gory and so realistic that it shocked the sensibilities of people– it seemed voyeuristic, in some people’s opinions.

3 Dec

The Emancipation Proclamation

Five days after the “victory” at Antietam, Lincoln changed the purpose of the Civil War with his issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation. With these few words, Lincoln changed the reason for fighting from the legalistic “preservation of the Union” to the moral and ethical imperative of “freedom and emancipation.” Frankly, many in Congress felt that Lincoln should have definitively rejected slavery much sooner, and there was the danger that Congress would act on this impulse whether Lincoln agreed or not.

As you read, consider the following questions:

1. What would have happened to slaves living in areas NOT in rebellion against the government, i.e. the Border States like Missouri, under the terms of this proclamation?

2. Why does Lincoln specifically list the areas to which this proclamation applied? Why are the areas of emancipation so tightly defined? Why were some counties (counties are called “parishes” in Louisiana) excluded?

3. Lincoln first wrote a draft of the proclamation in July of 1862. Why didn’t he issue it then? (Think– what was going on in the war at the time?)

The Emancipation Proclamation

Abraham Lincoln, September 22, 1862

By the President of the United States of America: A PROCLAMATION

Whereas on the 22nd day of September, A.D. 1862, a proclamation was issued by the President of the United States, containing, among other things, the following, to wit:

“That on the 1st day of January, A.D. 1863, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.

“That the executive will on the 1st day of January aforesaid, by proclamation, designate the States and parts of States, if any, in which the people thereof, respectively, shall then be in rebellion against the United States; and the fact that any State or the people thereof shall on that day be in good faith represented in the Congress of the United States by members chosen thereto at elections wherein a majority of the qualified voters of such States shall have participated shall, in the absence of strong countervailing testimony, be deemed conclusive evidence that such State and the people thereof are not then in rebellion against the United States.”

Now, therefore, I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, by virtue of the power in me vested as Commander-In-Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebellion against the authority and government of the United States, and as a fit and necessary war measure for supressing said rebellion, do, on this 1st day of January, A.D. 1863, and in accordance with my purpose so to do, publicly proclaimed for the full period of one hundred days from the first day above mentioned, order and designate as the States and parts of States wherein the people thereof, respectively, are this day in rebellion against the United States the following, to wit:

Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana (except the parishes of St. Bernard, Palquemines, Jefferson, St. John, St. Charles, St. James, Ascension, Assumption, Terrebone, Lafourche, St. Mary, St. Martin, and Orleans, including the city of New Orleans), Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia (except the forty-eight counties designated as West Virginia, and also the counties of Berkeley, Accomac, Morthhampton, Elizabeth City, York, Princess Anne, and Norfolk, including the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth), and which excepted parts are for the present left precisely as if this proclamation were not issued.

And by virtue of the power and for the purpose aforesaid, I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States and parts of States are, and henceforward shall be, free; and that the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.

And I hereby enjoin upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defence; and I recommend to them that, in all case when allowed, they labor faithfully for reasonable wages.

And I further declare and make known that such persons of suitable condition will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.

And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind and the gracious favor of Almighty God.

Link for further information:

Freedom at Antietam

The Antietam Battlefield

2 Dec

Ex parte Merryman and Ex parte Milligan

Be able to discuss with me: was the Lincoln administration and the Union army right in holding John Merryman or Lambdin Milligan (what an unfortunate name!)?

Here is a nice summary from PBS regarding Ex parte Milligan: http://www.pbs.org/wnet/supremecourt/antebellum/landmark_exparte.html

Here is a great discussion of the problem of habeas corpus in wartime in general: http://www.etymonline.com/cw/habeas.htm . This provides the background info to the case of John Merryman and Lambdin Milligan.

Excerpts from the decision of Ex parte Merryman (having to do with the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus by Chief Justice Taney:

“…The case, then, is simply this: A military officer residing in Pennsylvania issues an order to arrest a citizen of Maryland, upon vague and indefinite charges, without any proof, so far as appears. Under this order his house is entered in the night; he is seized as a prisoner, and conveyed to Fort McHenry, and there kept in close confinement. And when a habeas corpus is served on the commanding officer, requiring him to produce the prisoner before a Justice of the Supreme Court, in order that he may examine into the legality of the imprisonment, the answer of the officer is that he is authorized by the President to suspend the writ of habeas corpus at his discretion, and, in the exercise of that discretion, suspends it in this case, and on that ground refuses obedience to the writ.

As the case comes before me, therefore, I understand that the President not only claims the right to suspend the writ of habeas corpus himself, at his discretion, but to delegate that discretionary power to a military officer, and to leave it to him to determine whether he will or will not obey judicial process that may be served upon him.

No official notice has been given to the courts of justice, or to the public, by proclamation or otherwise, that the President claimed this power, and had exercised it in the manner stated in the return. And I certainly listened to it with some surprise, for I had supposed it to be one of those points of constitutional law upon which there is no difference of opinion, and that it was admitted on all hands that the privilege of the writ could not be suspended except by act of Congress….

The clause in the Constitution which authorizes the suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus is in the ninth section of the first article.

This article is devoted to the Legislative Department of the United States, and has not the slightest reference to the Executive Department….

But the documents before me show that the military authority in this case has gone far beyond the mere suspension of the privilege of the writ ofhabeas corpus. It has, by force of arms, thrust aside the judicial authorities and officers to whom the Constitution has confided the power and duty of interpreting and administering the laws, and substituted a military government in its place, to be administered and executed by military officers. For at the time these proceedings were had against John Merryman, the District Judge of Maryland–the commissioner appointed under the act of Congress–the District Attorney and the Marshal, all resided in the city of Baltimore, a few miles only from the home of the prisoner. Up to that time there had never been the slightest resistance or obstruction to the process of any Court or judicial officer of the United States in Maryland, except by the military authority. And if a military officer, or any other person, had reason to believe that the prisoner had committed any offence against the laws of the United States, it was his duty to give information of the fact and the evidence to support it to the District Attorney, and it would then have become the duty of that officer to bring the matter before the District Judge or Commissioner, and if there was sufficient legal evidence to justify his arrest, the Judge or Commissioner would have issued his warrant to the Marshal to arrest him, and, upon the hearing of the party, would have held him to bail, or committed him for trial, according to the character of the offense as it appeared in the testimony, or would have discharged him immediately if there was not sufficient evidence to support the accusation. There was no danger of any obstruction or resistance to the action of the civil authorities, and therefore no reason whatever for the interposition of the military. And yet, under these circumstances, a military officer, stationed in Pennsylvania, without giving any information to the District Attorney, and without any application to the judicial authorities, assumes to himself the judicial power in the District of Maryland; undertakes to decide what constitutes the crime of treason or rebellion; what evidence (if, indeed, he required any) is sufficient to support the accusation and justify the commitment; and commits the party, without having a hearing even before himself, to close custody in a strongly garrisoned fort, to be there held, it would seem, during the pleasure of those who committed him.

The Constitution provides, as I have before said, that “no person shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” It declares that “the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects against unreasonable searches and seizures shall not be violated, and no warrant shall issue but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched and the persons or things to be seized.” It provides that the party accused shall be entitled to a speedy trial in a court of justice.

And these great and fundamental laws, which Congress itself could not suspend, have been disregarded and suspended, like the writ of habeas corpus, by a military order, supported by force of arms. Such is the case now before me; and I can only say that if the authority which the Constitution has confided to the judiciary department and judicial officers may thus upon any pretext or under any circumstances be usurped by the military power at its discretion, the people of the United States are no longer living under a Government of laws, but every citizen holds life, liberty, and property at the will and pleasure of the army officer in whose military district he may happen to be found….”

Full text of Taney’s decision here: http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=442 He even brings up Aaron Burr!

You must be logged in to post a comment.