Remember to check the schedule under upcoming deadlines for how the semester has been adjusted due to EOC week.

ALWAYS INCLUDE DATES AND NAMES IN YOUR ANSWERS!!!

1. How did the end of the war affect most Southerners’ views regarding their understanding of the union and their “lost cause?” What happened to most Confederate leaders?

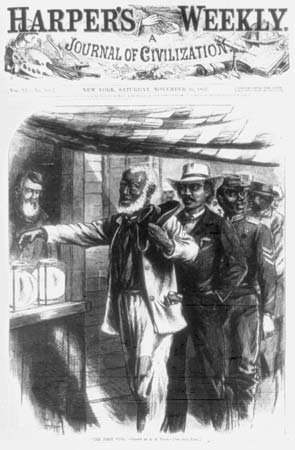

2. How quickly was emancipation implemented? What tasks did most freedmen then set out to do and rights did they claim for the first time?

3. Who were the Exodusters, and how many were there? Where were they headed, and why? Why did this movement end?

4. What was the full name and mission of the Freedmen’s Bureau? Who led it? What was it most successful at? How did white Southerners view it, and why was that kind of spiteful? What precedent did this agency set in terms of government responsibility for citizens? What did Andrew Johnson do to it and why? What impact did this have on his presidency?

5. What factors had led to choosing Andrew Johnson as Lincoln’s vice president in 1864? What group in particular did he champion as a politician? Who were the leaders of the Radical Republicans who opposed him so vehemently?

6. What were the basic differences between presidential and congressional Reconstruction. Start by comparing Lincoln’s plan for Reconstruction with the Wade Davis Bill. Which was more lenient, and why? How was Johnson’s plan unique, and which one was it most similar to? What is the “conquered provinces” theory, and who promoted it? Why were Congressional Republicans concerned about what would happen if the Southern states rapidly regained their representation in Congress?

7. What was the main purpose of the Black Codes? What were the major provisions of these? How did Northerners interpret these kinds of laws?

8. What were the main provisions of the Civil Rights Bill of 1866? What happened to this bill, and why? How is this law connected to the 14th Amendment? What did the 14th Amendment do? What did it say about Confederate officials? Which Southern states ratified the 14th Amendment in 1866?

9. What did the 15th Amendment do? Why were feminists disappointed in it (as well as with the 14th Amendment?

10. Discuss the activities of other groups besides the Freedmen’s Bureau that attempted to help freedmen—the Union League and the American Missionary Association, in particular. How did African American women get involved in securing rights for blacks, and what limits were placed upon them?

11. What were “Radical Reconstruction” governments’ accomplishments? How corrupt were they compared to governments elsewhere? What are scalawags and carpetbaggers?

12. Where, when how, and why did the Ku Klux Klan rise up originally? What were its goals? What attempts did the federal government make to suppress the Klan (include dates!!!!)?

13. Why did Congress finally attempt to impeach Johnson? What was the specific charge? Was this legitimate? How did Johnson escape?

14. How and why did we attain Alaska? Why was this important?

15. What were the basic philosophical controversies that were confronted during Reconstruction, besides how to readmit Southern states to full membership in the Union?

16. Make a chart detailing the intents of each of these laws:

– Military Reconstruction Act

-Tenure of Office Act

-Freedmen’s Bureau Act

-Force Acts

You must be logged in to post a comment.